In the current London building boom with its many towers with benign and amusing nick-names, it’s hard to imagine that residential towers in the UK were until recently viewed with considerable hostility. Yet even at the height of tower hatred there was a brief moment when a select few saw the tall residential block as a cultural status symbol.

In the hot summer of 1976 the dark flower that was punk rock blossomed in London. For two years its shoots had been appearing in council estates, squats, pubs and art schools in and around the city. When it finally emerged and began to spread like an unwelcome knotweed, the key to any cool punk rocker’s image was a London address. And the address that stated your authenticity as a true part of the movement was one within a tower block.

The London of 1976 was a city at the end of decades of decline. It had suffered from under-investment and a flight to the suburbs to escape crime, grime, poor housing and low educational standards. The population had fallen by more than 2.5m from its pre-war high, and the city was not seen as a place where “decent” people should live.

London was not alone, as this view applied to cities generally and was best illustrated by the New York authorities considering in the 1970s a policy known as “Planned Shrinkage”; a coordinated strategy to de-populate the less desirable areas of the city. From the 1960’s onwards the term “Inner City” was shorthand for a place best avoided.

The first wave of British punk rockers were the children of the inner city, but unlike many of its inhabitants who were keen to leave, they embraced it. Punk rockers embraced urban decay and all of its associated menace. Being part of a failing city tallied with their message of “no future” nihilism. To show their connection to the movement’s dystopian zeitgeist, the punk rockers used the city’s more negative aspects as the backdrop for their grainy brutalist portraits.

The building form that encapsulated this mis-en-scene, and that best symbolised everything that was considered wrong with the failed “inner city” was the council (Local Authority) tower block. Mainly built after the war as social housing to replace substandard building stock, tower blocks grew to dominate the skyline of many UK cities. Sold to the public as “streets in the sky”, their inhabitants soon became dissatisfied with living in vertical isolation away from the horizontal streets and communities they were used to. Dislike of the council block was not only due to social and psychological reasons. There were also very real physical problems due to low building standards caused mainly by cost cutting. It was these problems in tower block construction that ultimately resulted in the catastrophic collapse of part of East London’s Ronan Point block in 1968. Yet despite this, towers of this type continued to be built throughout the following decade.

Despite the tower block’s dominance of the British skyline, its appearance in popular culture in the 1970s was sparse. J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise was an aspirational destination for the rich (and The Towering Inferno was American). Other than these two reference points, the tower went largely unseen. And if these two towering palaces resulted in fictional dystopias that failed catastrophically, what hope was there for their very real low-budget equivalents? The council tower block had become an architectural persona non grata (the private residential towers of London’s Barbican didn’t appear until 1982).

However, because of its negative connotations, this building form very quickly became visual shorthand in the semiotics of punk rock. The Clash single “White Riot” featured a collage of tower blocks and police lines on its picture sleeve. The band’s rehearsal room was decorated with a mural of tower blocks and burned out cars painted by their art school-educated bass player. Other band members would later use Erno Goldfinger’s Trellic Tower in publicity shots and record sleeves to locate them culturally and geographically. Punk (and New Wave) bands including The Jam, The Boys and The Pigs featured tower blocks on their record sleeves. Punk fanzines and magazines used grainy images of tower blocks in torn graphics to sell the punk image.

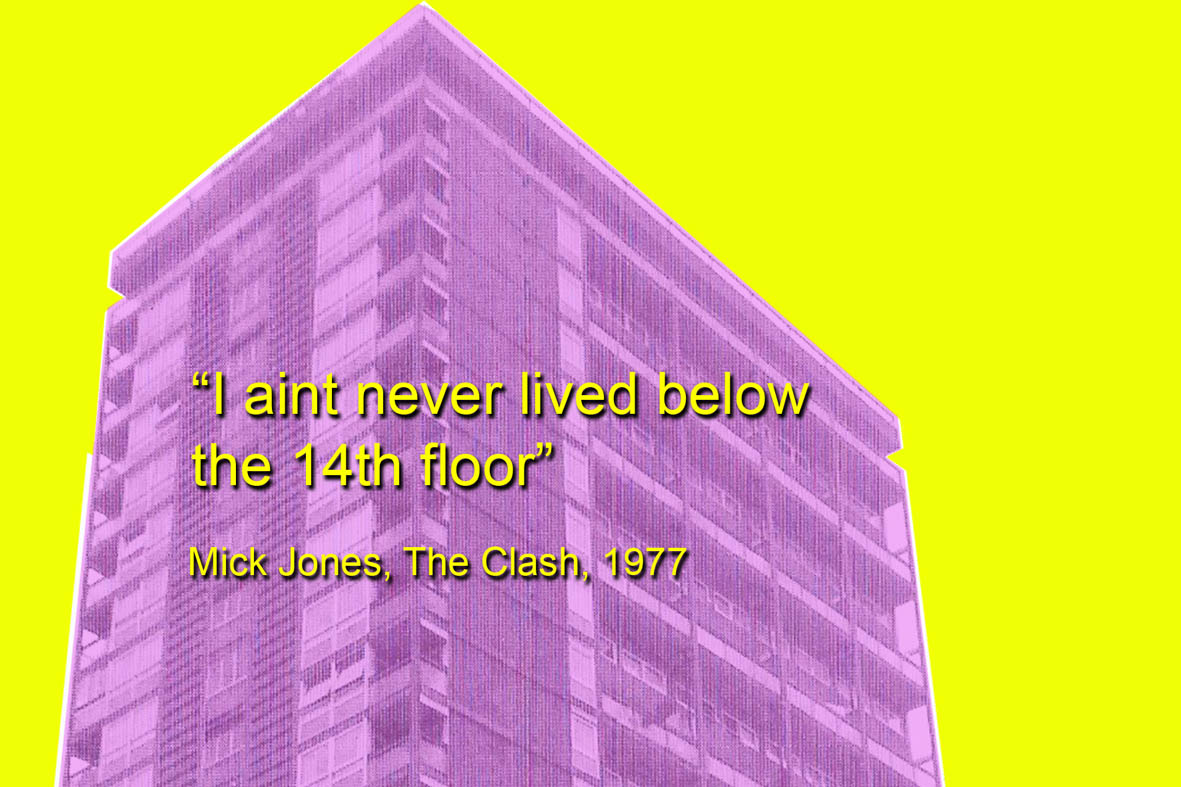

By 1977 the punk rock phenomena had become mainstream and had left the confines of the inner city. Suburban punks adopted the symbols used by the movement’s urban progenitors. Even BBC Radio 1 DJ Mike Read (the man who would later ban Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax”) had, in an earlier career as a musician, released a new-wave single called “High Rise” in which he sang about the building’s residents, including drag-queens, day-glo punks, a dirty old man and, of course, himself. It was therefore important for the creators of the punk scene to highlight their genuine urban credentials. In an interview in 1977, Clash guitarist Mick Jones asserted his authenticity in a movement that despised the poseur: “I ain’t never lived below the 14th floor”.

In an age long before The Shard. The Pinnacle, Principle Place, South Bank Tower, South Quay Plaza, One Nine Elms, etc, we knew exactly what Jones meant. For a brief moment, and to a select few, a council tower block home was aspirational. Yet despite this, dislike of the tower blocks by the general public, and more importantly by community politicians, continued. The 1980s and 1990s saw their systematic demolition. London boroughs such as Hackney proudly ran a campaign, supported by the local press, to remove the towers. Former tower residents would take part in raffles to chose a winner to press the detonation button for a building’s destruction. In some areas of the city, the council-owned tower blocks were almost completely removed. Now, with their physical presence largely gone, and little mention of them culturally, the council tower block is likely to become a mere footnote in urban history.

Since the millenium London has witnessed a reversal in attitude towards residential towers. There has been explosion in the development of private residential towers. These buildings, unlike their local authority predecessors, are very desirable, very expensive, and considered highly aspirational. However, it’s unlikely they will spawn a cultural movement the influence of which will be felt and analysed for decades after they’ve gone.

Roger Crimlis – June 2016.